IMANTS TILLERS

b. 1950

Lives and works in Cooma, New South Wales

Imants Tillers since the late 70’s has critiqued not only the art of the late 20th century Australian art but also international centres of the Western world. No discussion on postmodernism or appropriation can take place in Australia without reference to this significant artist.

Imants Tillers is the child of Latvian refugees who arrived in Australia in 1949, exiled from their homeland by war and political turmoil, part of the great post-war European diaspora. It is this experience of being displaced to a new land, isolated from cultural and personal histories, which has become a central component of Tillers’ work.

While he was born in Australia, in 1950, his first language was Latvian and therefore the questions he asks in his work are informed by the diasporic experience and longing—about place, relationships to the past and the self, of locality and identity. Together, the more than 100,000 canvasboards in Tillers’ paintings form a long poem with many verses. They are informed, as Tillers said of Colin McCahon, by “a constant tension between the search for meaning, the desire for transcendence and a pervasive, immovable scepticism.”

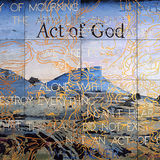

His landscapes are made up of fragments of borrowed images and of language—marks, words, phrases and names used to create the country, to give it form and place oneself within it. Using simple means—hundreds of small canvasboards combined into huge gridded paintings—they exist as part of a long, continuing series, or like a poem in many, fragmented verses.

Tillers’ works map a space of influence, combining, quoting and knitting together words, images and ideas, ghosts and other associations, with source material contributing fragments to his continuing, multi-part epic. The connections he draws together are at once his own and connections to a wider dialogue.

THE PHILOSOPHY OF DOUBT / 2017

The doubting and the doubting nothing.

Torn between skepticism and blind faith, I continue to pursue my concept of Metafisica Australe.

This exhibition is the next installment of a new body of work which attempts to find common ground between contemporary Western Desert painting and the metaphysical paintings of the 20th century Italian master, Giorgio de Chirico. It continues the premise of the exhibition 'Dreamings: Aboriginal art meets De Chirico' curated by Ian McLean and Erica Izett at the Carlo Bilotti Museum in Rome in 2014, in which seven of my works (from 1986 to 2014) formed a kind of bridge between the 20 works by Giorgio de Chirico which are on permanent display in the museum and the exhibition of Western Desert paintings from the Sordello Missana Collection from Antibes, France.

- Imants Tillers

One of Australia’s most internationally successful contemporary artists, Imants Tillers has exhibited widely since the late 1960s, and has represented Australia at important international exhibitions, such as the Sao Paulo Bienal in 1975, Documenta 7 in 1982, and the 42nd Venice Biennale in 1986, and won the Grand Prize at the Osaka Painting Triennial in Japan in 1993. In 2006 was the subject of a major retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. He was included in the Australia exhibition at the Royal Academy in London (2013).

Major solo surveys of Tillers’ work include Imants Tillers: works 1978 – 1988 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (1988); Imants Tillers: 19301, at the National Art Gallery, Wellington (1989); Diaspora, National Art Museum, Riga, Latvia (1993); Diaspora in Context at the Pori Art Museum, Pori in Finland (1995); Towards Infinity: Works by Imants Tillers, Museum of Contemporary Art (MARCO) in Monterrey, Mexico (1999); Imants Tillers: one world many visions, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (2006); The Long Poem, Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, Perth (2009) and Dreamings: Aboriginal Australia art meets de Chirico, Carlo Bilotti Museum, Rome (2014).

THE PHILOSOPHERS WALK / 2014

Since 1980, Tillers has composed his large grid paintings using small individual canvas boards and has sequentially numbered each one therefore connecting the individual parts to make the greater whole.

His imagery, both historic and contemporary, engages the notion that provincial culture derives its influences from imports of dominant cultures and concepts of displacement, both geological and spiritual. Taking inspiration from the late Albert Namatjira who, through his watercolours of Central Australia, found a way to repair some of the psychic and spiritual damage – what Kevin Gilbert has called ‘a rape of the soul’ – long endured by Aboriginal Australia.

NAMATJIRA

In the 1970’s the Aboriginal activist and writer, Kevin Gilbert wrote:

It is my thesis that Aboriginal Australia underwent a rape of the soul so profound that the blight continues in the minds of most blacks today. It is this psychological blight, more than anything else, that causes the conditions that we see on reserves and missions. And it is repeated down the generations.

The artist Albert Namatjira (1902 – 1959), I feel, found a way to repair some of this psychic and spiritual damage. His body of work – an art of healing – is the antecedent to the Papunya Tula art movement which arose like a phoenix from the despair of the desert displacement camps at Papunya in the early 1970’s, paving the way for the spectacular and unexpected blossoming of contemporary Aboriginal art which now occupies the mainstream of Australian art.

ALL HAIL NAMATJIRA!

Imants Tillers, 31 January 2014

Kevin Gilbert quoted in Robyn Davidson, “Tracks” (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), (first published 1980), p46.

NATURE SPEAKS

/ 2011

This exhibition is a kind of homage to the work of one of Australia’s great artists, Fred Williams. In the 1970’s as a young artist I thought that Fred Williams had painted the definitive, quintessential Australian landscape. At that time, neither I nor any of my artistic peers wanted to engage with the Australian landscape tradition – we found it conservative and stifling and besides, conceptual art offered a compelling alternative. However, since the 1980’s, Aboriginal artists have spectacularly reclaimed and reinterpreted this landscape tradition, inadvertently bestowing a new relevance on Williams’ work. In his distinctive abstractions of the Australian bush, which he typically organises into a somewhat chaotic pattern of hieroglyphs, we recognise some kind of arcane language (an “ur-text”) and we see that nature, indeed, “speaks” but not in a language we can comprehend.

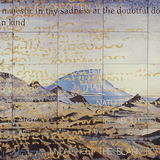

In recent years I have been experimenting with Williams’ imagery in my own work – of particular interest to me now is his last, somewhat maligned, Pilbara Series 1979-1981. A number of works in my exhibition, such as Melancholy Landscape VII 2011 and Thou Majestic: D 2011 draw on this series. In particular they reproduce the line of undulating mountains from his Karratha Landscape 1981. In this painting, the uncanny regularity of the contours of the mountain (or is it a hill?) reminded me of the very distinctive ‘journey lines’ in certain Aboriginal paintings and perhaps they suggest a hidden affinity that Williams’ art has with Aboriginal depictions of landscape. It is worth noting that the Pilbara series was an unusual departure for Williams into the ‘outback’ – artistic terrain that he otherwise left to artists such as Russell Drysdale, Sidney Nolan, and John Olsen to explore and colonise.

In my versions of Williams’ landscape the location is the Western Desert in Central Australia bearing the names of places such as Papunya, Tanami, Haasts Bluff, Kintore, Jupiter Well, and the names of the disappearing tribes of those areas – Warlpiri, Pitjantjatjara, Pintupi, Luritja. I am also somehow reminded of Albert Namatjira and the words of the German poet Novalis who observed that “every individual is the centre of a system of emanation.” Above all, for me, the desert is a metaphor for the self: “I shall become no more than movement or stillness or an idea of being – there is no-one here.” The desert is a tabula rasa – a surface on which the writing has been erased, ready to be written on again.

This exhibition also celebrates the 200th work in my own series Nature Speaks – Nature Speaks: CZ 2011. I began this series in September 1998 almost two years after I moved with my family from Sydney to the rural town of Cooma in south-east New South Wales. Ten years later after selecting this title, for what is arguably now one of my most significant bodies of work, I came across Antonin Artaud’s “50 drawings to murder magic”, published by Seagull Books in 2008. Written in a mental asylum in France, the last lines of what were Artaud’s last utterances are worth recounting:

“so my drawings reproduce

the forms

thrown up in this way

these worlds

of marvels

these objects

where the way passes

and what

used to be called the Great Work

of alchemy now

pulverised because we are

no longer in chemistry

but in nature

and I do believe

that

nature

is about to speak.”

Antonin Artaud

31 January 1948

LEAP OF FAITH

/ 2009

“Reality works in overt mystery” Jorge Luis Borges

This work consists of 120 canvasboard panels installed as a painting on a wall (one could call this ‘element1’) with 6 sculptures on plinths arranged in front of it (this could be ‘element 2’). Each of the 6 sculptures consists of 144 5” x 7” canvasboard panels cast in bronze. This new work incorporates an earlier painting, Leap of Faith, 1995, and transforms another, Tableau with closed loop, 1993, bringing them together and thereby creating a new totality.

Leap of Faith, 2009, spans 16 years from its gestation to its completion and comprises 984 panels (including the now inseparable bronze panels) and the work is numbered accordingly from 85904 – 86888.

The sculptural part of this work suggests to me a kind of ‘self-portrait’ but of the type explored by Jorge Luis Borges in his essay of 1922, The Nothingness of Personality, in which he wants “to tear down the exceptional pre-eminence now generally accorded to the self.” It is a ‘self-portrait’ which declares: “There is no whole self”; “I am like everyone else”; “the self does not exist”. And in being turned to bronze the immaterial, the evanescent, the dispersible canvasboard (self) becomes solidified, frozen and fixed forever.

There are echoes of this in the painting on the wall, in those panels which are inscribed by the word ‘NEZINAMS’ – meaning ‘unknown’ in Latvian. These are transcriptions from tombstones in a cemetery in Liepaja – my mother’s birthplace in Latvia, referring to the ‘unknown soldiers’ buried there, unable to be identified. As Ben MacIntyre wrote recently in The Times - London; “World War II tore Latvia to shreds. Annexed by the Soviet Union, occupied by Nazi Germany, then occupied again by the Red Army, brutalised, degraded and devastated, Latvia suffered dictatorship, colonisation and mass murder.” My father’s and mother’s lives were profoundly shaped by this tragic history and their trauma is part of the legacy that I have inherited. Leap of Faith is a tragic work. The strange but distinctive loop, which its two components (element 1 and element 2) share, is a kind of secret mark or cipher of destiny, which occurs in Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical painting Politics 1916 where it adjoins a map of some unfamiliar and indeterminate geography - a premonition, maybe, of the secret pact between Hitler and Stalin in 1939 that sealed Latvia’s desolate fate.

Leap of Faith is nevertheless infused with the redemptive spirit of the German artist Joseph Beuys. As Pierre Restany has written, Beuys came to be recognized in post-war West Germany as the intellectual model of the “good German”; “socialist and not communist; anarchist and not terrorist; poet of nature and lucid critic of the consumer society.” Part of his redemptive aura also “came with his involvement with the spontaneous practice of the expanded arts, a multimedia expansion of every kind of expression as advocated by the Lithuanian inventor of FLUXUS, George Maciunas.” Here there was a Latvian connection too, in the form of Valdis Abolins who took part with Beuys in one of the very first FLUXUS events - held in Wiesbaden in 1962 (Abolins’ name is celebrated in Leap of Faith). Indeed there are a number of references to Beuys in my work, in both imagery and text - in particular to his ‘action’ Manresa of 1966.

Leap of Faith also reproduces, in the original German, Beuys last powerful pronouncement that he transmitted by telephone from his sickbed, to a performance being enacted by Nam June Paik and Henning Christiansen in Hamburg in 1985. His brief but weighty words were a strong plea for the release of all the creative power that was held captive inside people (like the New Zealand artist/prophet Colin McCahon, Beuys spoke of “load–bearing structures”). For Beuys believed that ‘everyone is an artist’ and that it was this huge untapped reserve of creativity which could be humanity’s salvation if it could only be set free. Thus Leap of Faith is a tragic work that also contains much hope. Could this be part of the meaning of the enigmatic litany from the ‘action’ Manresa that can be found here and there in Leap of Faith:

“Here speaks FLUXUS / FLUXUS

Here speaks FLUXUS / FLUXUS

Now element 2 has climbed up to element 1

Now element 1 has climbed down to element 2

Now element 2 has climbed up to element 1

Now element 1 has climbed down to element 2

Repeat, repeat etc…”

IN TWO MINDS

/ 2007

Layering, repetition, variation are the central tenets of my art practice. What is always paramount is how the paintings are made rather than what they say. And in the last decade, the surgical scalpel rather than the paintbrush has been my primary tool. I have been cutting perhaps more than painting. But whatever I am doing, a total immersion in process is the secret key to the vast and sustaining body of work I have produced since 1981.

At that time I made a simple but profound discovery, which was the possibility of painting on canvas board panels. Not only on single panels but on many panels (up to as many as 300) arranged together in a grid to form a larger composite image. But the irony is that while I love the convenience and flexibility of the canvas board, I am not in love with the grid. The aesthetic of the grid is something I resist and struggle against, yet it is nevertheless a dominant aspect of my work.

In this new group of paintings for Adelaide, I move forward, yet stay in the same place. The twelve works span the interval between 77074 to 80708 - the cumulative total number of panels completed since 1981. 'Landscape' continues to be the dominant theme with references here to Albert Namatjira's various depictions of Haast's Bluff, to Hans Heysen's excursions to the Flinders Ranges and Rosalie Gascoigne's response to the Monaro region in South-Eastern Australia (where I live) as well as references to the faded sunflowers of Egon Schiele, to Gustav Klimt's slender birch trunks and to the silhouetted rose of Philipp Otto Runge. Consequently I seem to be in two minds as to where I should locate my psyche - next to the central Australian ghost gum or the Latvian birch tree - in Europe or in the Antipodes.

My Shadow of the Hereafter, the major work in this exhibition, is based on Hans Heysen's watercolour Land of the Oratunga, 1932. But today no landscape can be immune from the layering of language, human thought, culture and history. So I've added a kind of 'poetics of ghosts' to my version of Heysen's original - the names of vanished white settlements and erased Aboriginal societies. Thus a stark but sublime topography is witness to not only the transience of human existence and the failure of the local, but also the futility of human endeavour.

/ 2004

IMANTS TILLERS IN CONVERSATION WITH IAN NORTH -

(as published in Artlink, Vol 21 No 4, December 2001, pp. 35-41)

Artlink asked Ian North, a writer and artist, to interview Tillers for this issue, in view of his longstanding interest in both Tillers's work and the landscape genre generally. North had organised Tillers's first museum show, Still Life 2, Link exhibition no. 1 at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1974, and renewed his association with the artist by including him in the exhibition Expanse: Aboriginalities, Spatialities and the Politics of Ecstasy, which he curated in 1998.

Introduction:

Imants Tillers was early recognised as a leading conceptual artist in the 1970s and a pre-eminent postmodernist thereafter. He continues to work according to strategies he evolved during the 1980s, but seeking now an art of directly positive value as much as deconstructive quotation. He has become especially known for his Book of Power, the collective name for his multi-part works on canvas boards undertaken since 1981 and which is subject to complex possibilities of subdivision, recombination and indefinite extension, thus underscoring the interweaving character of his subject matter. He moved to the small country town of Cooma, New South Wales, in 1996. His work subsequently registered an interest in the natural environment and the surrounding Monaro region as an encultured landscape: the area had seen post-war migrants working on the Snowy River hydro-electric scheme in isolation from mainstream Australian society, a situation paralleling that of the artist's Latvian-born parents in Sydney. The artist also began revisiting Aboriginal art as a reference point as he had done in the 1980s, this time from a position of one learning about the land as well as mapping references within the international art arena.

Of the reproductions here, The Bridge of Reversible Destiny, 1990, gives the clearest indication of the elements of the Book of Power. The selection also includes Monaro, 1998, Tillers's first major work to register the grey, pink and bronze hues of the Monaro region. The other, more recent works also variously cite the work of Colin McCahon (the 'T' form, so dominant in another major work, Mexico, etcetera, 2001), a ladder (from Robert Fludd, 1574-1637), "The Throw of the Dice," a poem by Mallarme from 1897, and cherubs from the early nineteenth century German romantic, Philipp Otto Runge. Multiple elements come together to form statements about originality, chance and locality, articulated--a first for this artist--over extended series of works (Landprints, Nature Speaks). Mexico was occasioned by Cooma's association with Guerrerd, Mexico, on a 1945 homoclimatic map, while Nature Speaks: W, 2001, deploys the word "horizon" (ever shifting) over a clear suggestion of a real landscape.

Born in Sydney in 1950, Tillers completed a BSc course in architecture at the University of Sydney 1969-1972, gaining the university medal. He has not undertaken any other formal training, but regards working while a student on Christo’s Wrapped Coast, Little Bay, Sydney, as a formative experience confirming his interest in conceptual art and installation. Tillers held his first solo exhibition at the Watters Gallery, Sydney, in 1973, and his first solo museum show, Still Life 2, Link Exhibition no. 1, at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1974. Curated group exhibitions in which he has been represented include the XIII Bienal de Sao Paulo, 1975; Third Biennale of Sydney: European Dialogue, 1979; Popism, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1982; An Australian Accent, PS1, New York, 1984; Venice Biennale, 1986; Osaka Painting Triennale, Osaka (awarded Grand Prize), 1993; Antipodean Currents, Guggenheim Gallery, New York, 1995; Colonial Postcolonial, Museum of Modern Art at Heide, Melbourne, 1996; Expanse: Aboriginalities, Spatialities and the Politics of Ecstasy, University of South Australia Art Museum, Adelaide, 1998; and Empathy (co-curated by the artist), Pori Art Museum, Finland, 2001. Several major surveys of his work have been presented internationally, in London, Wellington, Riga and Pori. In September 1999 the Museum of Contemporary Art in Monterrey, Mexico, mounted the largest retrospective of his work to date: Towards Infinity: Works by Imants Tillers. He is represented principally by the Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide and the Sherman Gallery, Sydney.

* * *

Interview:

IN: We might start in the Monaro, working our way to the interior later ... Your Landprint works, for example, are liberally sprinkled with place-names, the sites in all cases of settler-culture cemeteries. You are clearly asserting the right of different traditions, as well as nature, to speak, a fact which leads me to your long-time interest in the great religious artist Colin McCahon, and the cultural layering to be found in his work. Were his starkly pared landscapes, the cosmic voids of his word and number paintings, dark precursors, as it were, for your take on the spareness, light and grace of the Monaro?

IT: That's a very poetic way of putting it. McCahon is, in my mind, without doubt a major 20th century artist, comparable to Rothko, Pollock or Beuys. It is astonishing to think that he produced his great art in the insular, provincial setting of New Zealand in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. And indeed, on several trips to New Zealand in the late 80s and early 90s, I developed a taste for those starkly austere, sleepy provincial towns that still dot the New Zealand countryside. So when I found myself in Cooma surrounded by those bare, bronze hills of the Monaro, it did strongly remind me of places in New Zealand, like New Plymouth, for instance. The Monaro is a unique and distinctive part of Australia, quite unlike the typical red-earth outback that is quintessentially Australian. I do feel indebted to McCahon's sensibility in choosing to live here. I have now been here almost five years and it is the readymade poetry of place names and geographical feature that has attracted me and become a new feature of my work. I have also become interested again in engaging with Aboriginal art since the move from Sydney and I'm keen to explore both Aboriginal and Christian claims to the land on the Monaro and elsewhere through the examination of respective sacred sites. Here, too, McCahon is prescient in his engagement with both Maori and Christian belief systems. The Maori references in McCahon lately have helped spawn--by inspiration or irritation--the most interesting contemporary New Zealand art, in work by young Maori artists such as Shane Cotton, Jacqueline Fraser, Peter Robinson and Michael Parekowhai.

Recently my own researches have led me to a country auction, at Adaminaby, near Cooma. Leafing through an old Monaro family bible from the 19th century I found the following McCahon-like passage: "lest for want of tillers the land be turned into a wilderness."

IN: My essay "StarAboriginality" was triggered by our conversation in 1998 when you suggested the word "post-Aboriginality," an exciting but troubling term, as a way of designating what the Expanse catalogue attempted to lay out: a new cultural condition in Australia as a consequence of the sweeping triumph of Aboriginal art and the concomitant opening of the non-Indigenous mind to Aboriginal culture. It seemed as if Indigenous art had leap-frogged from left field, or should I say outback, over non-Indigenous art--still languishing in pop-minimal-conceptual confusion--to rehumanise our post-human times, in the process neatly turning Australia's 'provincialism problem' on its head. How do you see these matters now?

IT: The success of the exhibition Expanse, I felt, lay in its capacity to define some wide parameters within contemporary art in Australia dealing with the themes of spirit, place and identity, in a way, somehow, that the chosen works generated an uncanny resonance with each other, in spite of the wide diversity of approaches and media. The other triumph of this important exhibition was that the paintings of the Aboriginal artist Kathleen Petyarre fitted so seamlessly, so naturally, into the context provided by the non-Aboriginal artists. The compatibility rather than the difference of her work was perhaps what suggested to us that we were moving into a new, dare I say it, 'post-Aboriginal' cultural condition in Australia.

After all, the Aboriginal renaissance in art has been with us now for thirty years and indeed, many of us have been looking at, thinking about and consciously or unconsciously absorbing the new forms of this art for at least twenty years. As you pointed out in "StarAboriginality," this is really the distinctively unique cultural situation in which Australian artists have found themselves in the late 20th century.

The landmark exhibition Papunya Tula in 2000--an exhibition that was as memorable as the best exhibitions I have seen in recent years, including Jackson Pollock at MoMA, Matisse in Paris and El Greco in Vienna--traced the genesis and development of Western Desert painting from its origins in 1971 to the present. I can only agree with Joan Kerr's assessment that Papunya Tula can lay claim to being an important contemporary art movement in the 20th century equivalent to, say, European cubism or American abstract expressionism. Papunya Tula art can also be seen as the catalyst for the veritable explosion in all the diverse forms of Aboriginal art from Arnhem Land barks to the postmodern paintings of Gordon Bennett or the photographs of Tracey Moffatt (the cosmological analogy to the Big Bang theory of the creation of the universe seems impossible to avoid!). So I think in this context one could speak of "post-Aboriginal" art also as that art that follows historically from this period 1971-2001 in which Aboriginal art unexpectedly and incredibly became the mainstream of Australian contemporary art practice. This is not to say that all art that follows will be "post-Aboriginal" but certainly that art which not only takes this Aboriginal art phenomenon into account but which also has been formed by it. This possibility is unique to our cultural situation here--unique to Australian artists.

IN: Some of your recent work, Mexico etcetera, for example, includes Aboriginal 'airport' paintings attached with Velcro to their surfaces, a step beyond and away from painted appropriation. But "appropriation" is now a doubly dirty word: avoided as being unfashionable by the art world with the type of disdain reserved in the real world for decayed prawns, it is also confused in debates around Aboriginal art between a once-faintly-scandalous, now neutral, art historical term for a postmodernist tactic, and as signifying the crime of theft. As I recall it, much of the adverse commentary you encountered in the 1980s and early 1990s for appropriating the work of, say, Timmy Tjapanardi or Michael Nelson Jagamara failed to take into sufficient account your recognition of Aboriginal art as a significant contemporary art phenomenon, nor the two-way potentiality of such recognition, as evidenced, for example, by the bounce Gordon Bennett gained from incorporating your work. What do you think now about the quite complicated interplays at work in these matters, and Howard Morphy's recent expressed idea that one should include within the category "Aboriginal art" other art which has influenced Aboriginal artists--yours, for example?

IT: Despite the artworld abandonment of the word "appropriation" in recent times, I personally am not afraid of it. In fact the forthcoming book on my own work by Graham Coulter-Smith has the word in its title-- Appropriation en abyme: the Postmodern Art of Imants Tillers.

As Coulter-Smith points out, "appropriation was a dominant force in international avant-gardist art throughout the 1980s to the extent that it has become synonymous with the concept of postmodern art." His book traces the scientific poetics which informs what he calls my "mode of deconstructive authorial appropriation"--such ideas as isomorphic mapping, Godelian undecidability and other ideas informed by systems theory, quantum mechanics and complexity theory. Part of the reason that appropriation is still a potent mode for me, when it has waned for many other practitioners, is that I have enlisted it for more complex purposes than simply authorial deconstruction. This partly stems from the fact that my canvasboard works are not just individual paintings but are also conceived as part of a larger totality--an ever-expanding whole which is the canvasboard system. Appropriation is a form of mapping in this context, so that while individual appropriations from the works of say Timmy Tjapanardi or from Michael Nelson Jagamara can be taken and criticised at face value, on another level they have a positional value within the totality of the canvasboard system which, while hidden from the viewer, is of an entirely different nature.

In any case the process of appropriation, even in its simple form, is not straightforward--it produces unexpected complexities, ironies and paradoxes. I would like to mention two such instances in relation to Gordon Bennett. The first occurred with respect to his appropriation of my work in his Nine Ricochets, 1990, which was a response to the appropriation of part of Michael Nelson Jagamara's Five Dreamings, 1984, in my Nine Shots, 1985. The Nine Ricochets won Bennett the Moet & Chandon Prize and helped propel his work to serious critical consideration and subsequently he has attained a substantial reputation which is reflected in his extensive presence in The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture. Because of his appropriation of my work, I am inextricably bound to him, like his shadow, so I also appear in the Companion, and my work, too, is part of Aboriginal Art! The other irony which I would like to mention is that circumstances have been such that I have now begun a series of collaborations with Michael Nelson Jagamara. This collaboration has been facilitated by Michael Eather and his Campfire Group in Brisbane--The process has just begun and the direction it is taking is still unclear.

IN: You mentioned to me a year or so ago that you were planning to venture the centre of Australia for the first time, Uluru and all that, a consequence of an intimation that it would reinforce your aspirations towards an art of more directly spoken positivity--and perhaps trigger another of your periodic forays as a writer. Are you ready, yet, to report back?

IT: Yes, I did go to the centre of Australia--twice, both in 2000. Firstly I was invited to fly in a light plane with three others across Australia from the south-east to the north-west: from Bendigo to Coober Pedy, William Creek, Lake Eyre, Alice Springs to Hall's Creek, Kununurra and Faraway Bay in the remote Kimberley area. This was an initiation into the red expanse of Australia's physical and psychic interior. A wonderful experience: I produced a flow of consciousness notation, both verbal and visual, of this experience--it was particularly intense during the three hours it took to traverse the Tanami Desert. It now forms part of an intermittent diary which I keep as my "Daily Research."

Then, several months later, I took all of my family to the spiritual centre of Australia; Uluru, which was truly amazing. I haven't quite got to grips with these experiences yet in terms of specifically new work but I sense that the "Canvasboard System" has already happily accommodated these experiences and I can see myself moving tentatively into new directions--mapping new psychic terrain.

Endnotes:

Interview conducted by fax and telephone exchanges, 4 - 9 November 2001

Expanse, University of South Australia Art Museum, Adelaide, 1998. The exhibition included work by Jon Cattapan, Rosalie Gascoigne, Antony Hamilton and Kathleen Petyarre as well as Tillers

This form is also to be found, inter alia, in the other four works in Tillers's Diaspora series, 1992 - 1998, of which Monaro is the culmination. The use of the 'T' form, or Tau cross, refers to a form found repeatedly in McCahon, but also refers to the initial letter of Tillers's family name. The 'T' images in Monaro also relate to many small paintings the artist has made of the Monaro landscape

Fludd's ladder has also lent its form to a sculpture by the artist, The Attractor, 2001, painted steel, 2500 x 370 x 70 cm, plus engraved stone elements (in progress), for the Sydney Olympic Cauldron Relocation and Overflow Park project at Homebush Bay, Sydney.

The Nature Speaks series, for example, is to total 100 works

"Monaro—South Coast Region," Homoclimatic Map, N.S.W. Forestry Commission, Government of New South Wales, 1945

Genesis. 47:19 DV

Conversation with the author c. 10 August 1988, about his essay "Expanse: Aboriginalities, Spatialities and the Politics of Ecstasy," in catalogue of same title, University of South Australia Art Museum, Adelaide, 1998, pp. 1 – 15. See also "StarAboriginality," in Charles Green (ed.), Postcolonial plus Art: Where Now? Artspace Visual Arts Centre, Sydney, 2001, n.p. The word "post-Aboriginality" is entirely positive in its intended connotations, but needs careful explanation to avoid implications of negativity

Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius, curated by Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, in association with Papunya Tula artists, 2000

Joan Kerr, "Papunya Tula: a great contemporary art movement," Art Asia Pacific, Issue 31, 2001, p.33

Of the two panels in Mexico, etcetera, both purchased at Sydney airport, one is painted by Corinna Nanpijinpa Ryan and the other by an unidentified Anmatyerr artist

Howard Morphy, Aboriginal Art, Phaidon Press, London 1998, p. 420

Graham Coulter-Smith, Appropriation en abyme: the Postmodern Art of Imants Tillers, 1971-2001, Fine Art Research Centre, Southhampton Institute, Southhampton, forthcoming

Sylvia Kleinert and Margot Neale (eds.), Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, Melbourne 2000

E.g. Imants Tillers, "Locality Fails," Art & Text 6, Winter 1982, pp.51 - 60; and "In Perpetual Mourning," ZG/Art & Text, Summer 1984 pp. 22 - 24, 27. For further references, see Wystan Curnow, Imants Tillers and the 'Book of Power,' Craftsman House, Sydney, 1998, p. 154