CHRISTIAN LOCK

b. 1969

Lives and works in Adelaide, Australia.

Christian Lock was born in 1969. He completed an Advanced Diploma of Art, Applied & Visual, North Adelaide School of Art, Adelaide (1999); Bachelor Visual Arts, SA School of Art, University of South Australia, Adelaide (2000); Honours, Bachelor Visual Arts, SA School of Art, University of South Australia, Adelaide (2001); Masters Visual Arts, SA School of Art, University of South Australia, Adelaide (2006). Exhibitions include The Substation Contemporary Art Prize, The Substation Centre for Art & Culture, Victoria (2011); CACSA Contemporary 2010: THE NEW NEW, Contemporary Art Centre of SA, Adelaide (2010); Wynne Prize for landscape painting, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (2008).

Collections include Artbank, Sydney; Art Gallery of South Australia & private collections.

'To describe Christian Lock's work as a painting does not quite encompass the nature of this practice. He works with painting, interrogating its components and parts, examining their roles and possibilities before pulling them back together in the final object. The impulse to push past the traditional limits of painting draws a lineage from Contemporary Abstract painting to the ideas of late 1960's Modernist Abstraction and "Light and Space; art of Californian Minimalism". Referred to as "Finish Fetish: artists they aligned their aesthetics with Californian car and surf culture, appropriating new innovative industrial materials such as resins, plastics and auto enamels; the resulting reflective forms acknowledged light and space as integral considerations working to remove the boundaries between painting, sculpture and architecture.

His recent work employs a range of novel analogue and digital painting methods in combination with industrial substrates, plastics and resins, testing their gestural and spatializing qualities and their potential to break free from a two- dimensional plane while reassessing painting's physicality.

Sampling and repurposing a diverse range of forms, motifs and strategies from Modernism, the industrial processes and materiality of minimalism and hybrid language of Post Modernism and Pop Culture, the paintings become 'remixes'; creating new tracks from fragments of old songs, full of quiet nods to the history of painting whilst exploring its possibilities and suggesting its potential future.'

TECHGNOSTIC TRANSMISSIONS

/ CHRISTIAN LOCK

/ DECEMBER 6 - DECEMBER 22, 2023

Christian Lock works in the “expanded field” of abstract painting. His past practice has integrated subcultural influences, especially from surf culture, with gestural expression, colour-field painting, collage and assemblage, locating them alongside the metaphysical concerns of early twentieth-century abstraction. His new work presents ambitious experiments with materials, surface, texture, and spray-painted pigment. These are entry points to explorations of intense visual experience, especially colour experience. For Lock, like the early twentieth-century abstractionists, colour brings with it a spiritual awareness. Lock also finds spiritual potential in technologically-mediated flows of energy and information. The colours, grids and geometric elements of his new work draw on these ideas, giving powerful and moving form to ideas that are at once visual, technological and cosmic.

Colour

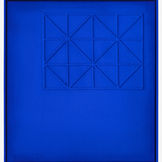

Lock tells me that the intense blue that he uses in this series comes from the blue colour one can see when you press or rub your closed eyes. Such colour effects are called phosphenes. For some, these colours are just the electrical flickering of the visual system as it is prodded and pressed. For Lock, these colours are a symptom of another reality beyond or outside our physical world. Over a century ago, Kandinsky described similar beliefs. When one experiences colours unattached to or independent of physical objects in the world, we see the non-physical, spiritual character of colour. This was most apparent in his synaesthetic experience of colour: intricate arrangements of colours prompted by music but attached to no physical surface. More recently, philosophers have argued for the non-physical character of colour experience. In a famous thought experiment, devised by philosopher Frank Jackson, we are asked to imagine a scientist, named Mary, who knows everything about the physics of colour and its optical and neural processing, but has not herself experienced colour because for her entire life she has remained in a room painted and furnished only in black and white.[i] (And, we will want to add, she has never pressed her eyes and seen Lock’s coloured phosphenes.) Jackson asks, does Mary experience anything new when she leaves her black and white room for the first time, and sees the world in colour? Jackson says yes – she learns what it is like to see all the colours, the intense blue of the sky, the yellow of the sun, and so on. But Mary already knows every physical fact about colour vision. So, what is it that she has learned? She has learned a non-physical fact – and it follows that what she has learned, what blueness is like as an experience, is non-physical. It is a short jump from there to understanding our experiences of colour as having a meaningfully spiritual character.

Much of Lock’s colour in these works is made with spray paint, sometimes applied over patterned and textured prints. The paint itself is matt, and sprayed on to the surface, it produces a soft quality, like pure pigment. The non-reflective character of the paint ensures that no reflection diminishes the purity of its colour. Lock also tells me that ultramarine blue has a slightly fluorescent character. It absorbs ultraviolet light and transmits some of that energy as blue light. I’ve failed to find anything about this in the scientific literature on pigments, but looking at the intense blues of some of Lock’s paintings here, I find it easy to believe. Lock’s intense blues also remind me of the intense ‘self-luminous’ hues that Paul Churchland calls ‘chimerical colours’, and I wonder if similar effects enhance some of Lock’s intense colours.[ii] However these intense effects are produced, they have a quality that seems, phosphene-like, somewhat detached from the world of physical objects, emanating from the canvas, encouraging us to acknowledge their existence as pure sensation.

Geometry and grids

If one continues to press or rub one’s eyes, one may see grid and mosaic-like geometric patterns. These can also be seen in lucid dreaming, or in response to sensory deprivation, strobing lights or psychedelic drugs. The psychologist Heinrich Klüver identified the various forms that these patterns can take.[iii] For those who see them, they can suggest glimpses of otherworldly architecture and decoration. The geometric elements in Lock’s works suggest such fragments – pieces of moulded latex patterned with a grid and laid over the canvas, or patterned with a more complex geometry and integrated within the canvas’s powdery surface. All suggest structures that extend – invisibly – further, perhaps indefinitely. For me, they recall the glimpse that the traveller in the Flammarion engraving gets of a world of neo-Platonic forms as he lifts the curtain surrounding the mundane world of appearances.

Anonymous, Flammarion engraving, 1888.

Techgnostic transmissions

Geometry and grids are also features of the modern, technological world. They are present in real physical forms, large and small, in concrete, steel and wiring, and in the invisible but no less physical flows and networks of energy and information. For Lock, the geometries and patterning that appear in his works are especially associated with networks of energy and information. Here, Lock’s ideas shows an affinity with those of Erik Davis, whose 1998 book, TechGnosis: Myth, Magic and Mysticism in the Age of Information, drew attention to the many parallels underlying thinking around information technology and ancient spiritual ideas. He focused especially on Christian Gnosticism, which put great store in secret knowledge and mystic experience – ideas vividly visualised in the Flammarion engraving. Of course, technology, as ordinarily understood, is a physical phenomenon. But Davis shows that underlying the thinking of many of its most visionary proponents are impulses that have an affinity with strands of early Christianity: a disdain for the body, a fear of death, and a desire for immortality. For Davis’s “techgnostic”, these impulses drive a desire to become one with technology, and to identify the technological with the spiritual.

How far can we follow such ideas? Some say that we are becoming fused with technology already. For philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers, our minds may already extend beyond our skulls to the technology that we depend on for cognitive processes such as memory, calculation and visualisation.[iv] We often “outsource” these activities to technology: social media sites hold our memories, computers enhance our ability to calculate, and CGI and AI aid our ability to visualize. So, much cognition goes on outside our skulls. Thus, for Clark and Chalmers, our minds – which is also to say our selves – may extend beyond our bodies into technology. We may already be cyborgs of a kind: amalgams of flesh, technology and invisible flows of energy and information. Clark and Chalmers’s thinking does not go quite so far as Davis’s, but their ideas are consistent. As Davis says, “information technology transcends its status as a thing, simply because it allows for the incorporeal encoding and transmission of mind and meaning.”[v]

Lock thinks of his works as “techgnostic transmissions”: transmissions of mind and meaning that hint at the kinds of understandings I have sketched here. His works present the viewer with the non-physical character of colour, and suggest a world in which one’s sense of self extends beyond one’s body into abstract, technologized spaces. Look at these works, and something else will be straightaway apparent. They show that these revelations in our understanding of reality, and changes in our sense of self, need not be threatening, but can be affirming, life-enhancing and oceanic in feeling.

– Michael Newall, November 2023

Michael Newall is a writer and researcher. From 2004–20 he taught at the University of Kent, Canterbury, where he held roles including Director of the Aesthetics Research Centre and Head of the History of Art department. He has published two books: What is a Picture? (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), and A Philosophy of the Art School (Routledge, 2019) which won the Outstanding Monograph Prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Currently he is researching questions around colour, and his recent publications in this area include ‘A Study in Brown’ (Synthese, 2023) and ‘Painting with Impossible Colours’ (Perception, 2021). He is Co-Director of The Little Machine, a space for contemporary and experimental art, which he curates with Eleen Deprez.

[i] Frank Jackson, ‘Epiphenomenal Qualia’, Philosophical Quarterly 32, 1982: 127–36.

[ii] Paul M. Churchland, ‘Chimerical Colors: Some Phenomenological Predictions from Cognitive Neuroscience’, Philosophical Psychology 18, 2005: 527–60.

[iii] Heinrich Klüver, Mescal and Mechanisms of Hallucinations, University of Chicago Press, 1966.

[iv] Andy Clark and David J. Chalmers, ‘The Extended Mind’, Analysis 58, 1998: 7–19.

[v] Erik Davis, TechGnosis: Myth, Magic and Mysticism in the Age of Information, Harmony Books, 1998: 4.

SYDNEY CONTEMPORARY

/ 2022

SELECTED IMAGES / 2017 - 2020

13th INTERNATIONAL CAIRO BIENNALE / 2019

To describe Christian Lock's work as a painting does not quite encompass the nature of this practice. He works with painting, interrogating its components and parts, examining their roles and possibilities before pulling them back together in the final object. The impulse to push past the traditional limits of painting draws a lineage from Contemporary Abstract painting to the ideas of late 1960's Modernist Abstraction and "Light and Space; art of Californian Minimalism". Referred to as "Finish Fetish: artists they aligned their aesthetics with Californian car and surf culture, appropriating new innovative industrial materials such as resins, plastics and auto enamels; the resulting reflective forms acknowledged light and space as integral considerations working to remove the boundaries between painting, sculpture and architecture.

His recent work employs a range of novel analogue and digital painting methods in combination with industrial substrates, plastics and resins, testing their gestural and spatializing qualities and their potential to break free from a two- dimensional plane while reassessing painting's physicality.

Sampling and repurposing a diverse range of forms, motifs and strategies from Modernism, the industrial processes and materiality of minimalism and hybrid language of Post Modernism and Pop Culture, the paintings become 'remixes'; creating new tracks from fragments of old songs, full of quiet nods to the history of painting whilst exploring its possibilities and suggesting its potential future.

SPACE JUNKIE / 2018

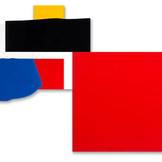

Glossy surfaces and abstract, amorphously rounded or lazy geometric shapes characterise the new paintings by Christian Lock. The paintings elegant in themselves are as much constructions as they are paintings, directly referencing Modernism’s pure beauty.

The imperfect smoothness of the surfaces and their crisp, limit palette call to mind Mondrian, Reitfveld, de Stijl or even Malevich — possibly Modernity’s most prominent abstract artists working in the first quarter of the 20th century. In creating these new works Lock, revisits seminal works from the early Modernists: scrutinising forms and colours and infuses a new energy and materiality into the mix.

This is not a sentimental retrogressive approach to art making, Lock has for sometime sort to extend the possibilities of painting, experimenting with materials, systems of holding a 2 dimensional surface in space, or methods of production outside the traditional conventions.

- Paul Greenaway

To describe Christian Lock as a painter does not quite encompass the full nature of his practice – Lock works with painting, interrogating its component parts, examining their role and possibilities, before pulling them back together in the final object. This impulse to push past the traditional limits of painting draws a lineage from Lock to the ideas of late 1960s Californian Minimalism, or Light and Space art. Referred to as the ‘Finish Fetish’ artists, those working in this manner aligned their aesthetics with the car and surf culture prevalent in California, appropriating new and innovative industrial materials such as resins, plastics and auto enamels. The resulting reflective forms acknowledged light and space as integral considerations, working to remove the boundaries between painting, sculpture and architecture.

Lock’s recent work pushes these materials, testing their gestural qualities and their potential to break free from the two-dimensional plane. Their molded surfaces appear casual, even accidental, but time spent with them reveals their careful composition. The works in Space Junky are a balance of experimentation and control: areas of deliberate molding steady the liquid drips; smooth and glossy, mechanical geometry provides a counterpoint to liquid biomorphic forms.

Gillian Brown,

Curator,

Samstag Museum of Art,

Uni of South Australia, 2018

QUICKSILVER / 2016

Quicksilver: 25 Years of Samstag Scholarships celebrates the 25th anniversary of Gordon Samstag’s remarkable bequest, which led to establishment of the Anne & Gordon Samstag International Visual Arts Scholarships. The greatest gift expressly given towards the development and education of Australian artists, the scholarships provide Australia’s most promising artists the opportunity to study overseas, at any institution of their choosing.

Thanks to Gordon Samstag’s generosity, over 130 Samstag Scholars have already benefited from a unique international experience that introduces them to new networks of artists, curators and visual arts professionals, to become key names in our nation’s cultural pantheon.

Quicksilver reflects on the impact of the Samstag Scholarships on the trajectory of Australian contemporary art. Pivotal works by six distinguished scholars – Mikala Dwyer, Nicholas Folland, Shaun Gladwell, Christian Lock, Nike Savvas and Linda Tegg – highlight the exciting talent that the University of South Australia has had the pleasure of assisting over the last quarter century.

Quicksilver is a Samstag Museum of Art exhibition developed for the University of South Australia’s 25th birthday celebrations, curated by Gillian Brown.

/ 2015

Painting, like music, belongs more to time than space. The physical intelligence of our bodies is a recording of past occurrences into our flesh. Even our analytical minds are formless, until given shape by some outside prompt. Our echoes to stimuli are lined with complex patterns, built up through seemingly unrelated events. Tumultuous and sometimes violent imagery is a given.

My work involves the dispersal of paint and pigment by air. If a viewer were to observe the studio process, they may consider that nothing has been added that was not already present. The movements from the floor to the wall could appear as repeated resurrections. But could also be considered an inversion, vertiginously holding up the viewer. Monochromatic images help us to see things in greater definition.’

/ 2013

Christian Lock’s recent works take us on a speculative journey. We see pearlescent biomorphic forms floating across fields of black abstract patterns on plastic. The materials appear animated, with the plastic draped loosely over exposed timber stretchers. At first the eye travels with some uncertainty and enters a kind of perspectival tug of war between seemingly disparate forms and surfaces. But slowly we notice Lock has poetically tempered chaos with control.

Lock is relentlessly engaged with testing the limits of the painting process. He works like an alchemist open to the transmutation and magic that occurs through the manipulation of matter. At the core of his creative process is an experimental procedure. Lock creates ‘paint skins’: brush strokes of varying sizes and shapes applied to sheets of plastic, which are later removed and reapplied. These skins become interchangeable parts that are systematically arranged on the studio floor like collage. Through this process Lock works counter-intuitively in what he considers to be a higher state of consciousness, guided by the tonalities and rhythm of his materials.

His approach combines formal control and free-flowing randomness to find pictorial balance. The surfaces are reminiscent of the control of hard-edge abstraction and the spontaneity of abstract expressionism. The systematic and precise abstract patterns are balanced with their spontaneous and gestural counterparts to achieve an image of structure and spatial depth. The geometric patterns flatten the pictorial surface while the swirling gestures allude to a deep abyss. Flat solid coloured shapes are sparingly placed over the top of a monochromatic base to further enliven the scene. Their shallow depth of field is confronting – as Andrew Frost has noted, they disturb the illusion of infinite space ‘like a sticker placed over a photo’1.

The rest of the palette appears mystical and meditative, entering the realm of the artificial and psychedelic. The monochromatic layers created through digital scanning processes have a ghostly presence, like X-rays of the human body, film negatives or storm clouds. This dark palette is not new to Lock: in 2003 he completed a series of paintings featuring holographic stickers with black synthetic polymer paint, highlighting the play between the visible and the void. Lock embraces the luminescent qualities of black when placed against vibrant colour, and seems to share a view similar to Kandinsky who regarded black to be leading an existence away from that of simple colour.

Lock’s paintings are no longer content to rest flat on a wall and instead occupy three-dimensional space. He is revisiting the late 1960s modernist exploration of ‘painting in space’. However, rather than reshaping or eliminating the frame, Lock takes on the rectangle by exposing, overflowing or displacing it. In some cases the stretcher even becomes a compositional device. By these means Lock separates the basic elements that typically hold a painting together: the stretcher and the canvas.

Plastic is introduced as the binding material. In his 1957 classic essay ‘Plastic’, Roland Barthes observed that plastic is ‘more than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation… it is less a thing than the trace of a movement’2. In line with Barthes’ view, Lock hasn’t fixed his plastic into a final state but has chosen to leave the material open to change and manipulation. He has previously said that his works ‘allow one to see oneself slowly morphing and changing along with them, making each viewer aware of the self’s potential to change and flow’3. One wonders if Lock aims to manipulate the mind as he does matter, revealing them both as infinitely malleable.

Perhaps the most engaging aspect of these works is how the ethereal properties of the materials shift with the conditions of perception. The holographic paper and glitter,4 for instance, reflect the surrounding hues and appear to change depending on where the viewer is standing. Likewise the plastic layers reflect external light and require the viewer to move to see beyond their own reflection. It is as if the works demonstrate the synthetic character of a hallucinatory state and engage with the late 1960s ideas of psychedelia. In The politics of ecstasy, 1968, psychologist Timothy Leary famously promoted LSD consciousness, describing it as a state of flux and elation that could release the mind from the illusions of conventional consciousness and provide access to the expansive realms of the ‘Mind at Large’5. While hallucinogenic drugs are not the impetus for Lock’s work, he expresses a similar desire to expand consciousness. He urges us to follow an unknown path into transcendence and quite simply ‘go with the flow’.

FOOT NOTES

1- Andrew Frost, untitled essay, Christian Lock website, 29 September 2013, http://www.christianlock.com/about-2/

2- Roland Barthes, 'Plastic', in Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: The Noonday Press, 1972), p.97

3- Christian Lock, ‘Ghost in the Machine: Gesture and sublime in a postmodern age’ (masters thesis, University of South Australia, 2007), p.47

4- These materials stem from Lock’s background in surf culture, but he has explained recently that ‘surfing is no longer the major force behind my paintings’. Christian Lock, in conversation with Elle Freak, Adelaide, September 2013

5- Timothy Leary, The politics of ecstasy (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1968). ‘Mind at large’ is a concept from Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception, 1954, and Heaven and Hell, 1956.

/ 2011

I like a lot of things about Christian Lock’s paintings. I usually visualize them lined up in his large studio to the south of the city, where he works across multiple canvases. The museum scaled, pooled, and impasto-ed paintings speak of course of European and North American abstraction. But I like their other, more local references, too. And I like his attitude.

I also like Lock’s titles. They champion narrative and humour above the purity and universality that you might expect from High Modernism. It is easy to see them as an equally important component of the work. They are ironic, always coming from a highly individualized perspective. They make repeated nods towards death and other highly dramatic narratives. Most importantly, the titles point us towards a broader cultural focus.

Lock’s father was the artistic director of the seminal surf clothing brand Golden Breed, whose invention of sci-fi fantasy surf art is a legacy for these works. Sci-Fi and Surrealism are often recognised as related - respective by-products of internal and extraterrestrial scientific exploration. In Australia, we might add another triad - surfing - which exists as a very immediate and accessible entry into transcendence.

Also perhaps important is the rapid transcendence available through drugs and popular culture. In works such as Taste the Space Candy we can see the imprints from graphic design in magazines or video clips. At other times holograms, clothing designs, or car paint effects manifest themselves. Glitter paint was invented in South Australia (the product of a rivalry between Murray River speedboat owners, cooked up in a suburban workspace - much like Lock’s).

Lock’s works are not mere collages or sampling. The idea seems erroneous - as wrong as the phrase 'surfing the internet' has always been. Just as in that analogy, the body is inert when online; in surfing and large-scale painting, one is always fully embodied. In Lock's case, the body is equally important when viewing his works. Also, surfing is a creative act, and reading online could only ever be considered active in relation to, say, television. When I think of the function of Lock’s paintings, they stand in for a more creative, digested and active engagement with culture.

Abstract Expressionism’s ‘truthiness’ was aimed not only at the materiality present in the current act of painting, but in reappraising works that preceded them. It saw itself as a general raising of consciousness. If we think of abstraction and Lock’s works, they perhaps more function like a dream. Easy and difficult things have been brought into a strange continuum. Light appears without a source. When viewed in an exhibition, their homogeneity both hides and reveals the sequential moments of their construction. And just as in a dream we are unsurprised by sudden counter-logical appearances. Rather than a scientific raising of consciousness, I much prefer Lock’s wilful and mystical distortions to it.

/ 2009

These current paintings attempt to conjure up fictive spaces and abstract narratives. While these works remain open to subjective perception, they suggest states of metamorphosis, and record and evoke sensations of submersion, flight and weightlessness. I continue to combine a range of experimental approaches to painting, with a strategy of sampling and remixing as a fluid means of developing aesthetic and conceptual frame works.

/ 2007

".. I want to have film of a surfer right at that point moving along constantly right at the edge of the tube. That position is the metaphor of life to me, the highly conscious life. That you think of the tube as being the past, and I’m an evolutionary agent, and what I try to do is to be at that point where you’re going into the future, but you have to keep in touch with the past ... there’s where you get the power; ... and sure you’re most helpless, but you also have most precise control at that moment." 1

Timothy Leary

In November 1886, a regional French newspaper reported the astonishment of several Breton fishermen, who had observed ‘a man, dressed like them... stubbornly painting, during the storm, upon canvases fixed to an easel lashed to the rocks with ropes.’2 The artist was Claude Monet, who in 1886 undertook a journey to Belle-Ile-en-Mer – a remote island off the coast of Brittany – where he painted a series of seascapes of its dramatic rock formations and wild churning waters that are emblematic of eighteenth and nineteenth century notions of the sublime. In the historical discourse of the sublime, the sea – with its capacity to inspire awe and terror – figures prominently and for Schopenhauer, for example, other natural phenomena paled beside the sheer intensity of the oceanic sublime.

The Monet episode echoes the legendary (separate) exploits of Joseph Vernet and J.M.W. Turner, who were driven to experience a storm at sea, whilst lashed to the mast of a ship. Exposure to the power of nature is even more direct and intense – perilous, yet also potentially exhilarating – for the surfer. ‘One of the great lessons that you learn in the ocean is that while you are totally insignificant to the total mass, you can survive in it by being part of it.’3

The subjective paintings of Christian Lock are predicated on a lifelong engagement with surfing and the associated paraphernalia of surf culture – surfboard production and surf art as well as comic books, films and surfing mythology. Two distinct strands – large acrylic works on canvas and the smaller surfboard paintings, in which expressive brushwork is contained within a sheath of clear, polished resin or (more lyrically) Lock’s ‘rolling waves of liquid glass’4 – have continued to evolve within his art practice. In utilising a variety of inventive techniques to ‘push liquid around to create forms’, Lock equates his visceral gestural markings with the swooping manoeuvres of the experienced surfer – referring to the surfboard as a ‘brush.’

Like Lock’s ongoing leitmotif of a seductive biomorphic (flower-like) form in One Sheet of Strawberry Fields, One Black Caravan, One Last Coffin Ride (2007), the black chrysalis-like, Surrealist-inspired motif of the large brooding, aubergine painting Out of Your Depths suggests the possibility of metamorphosis. These ambiguous hovering and mutable forms – also viewed by the artist as transitional spaces, as portals or thresholds (to transcendent experience) – reappear in more tranquil and cool (aqueous?) mode in George Greenough Versus Timothy Leary, wherein the introduction of fine brushwork accentuates a contrasting sense of the ethereal.

The impetus for the surfboard paintings came not only from Lock’s observation of techniques associated with the production of resin surfboards– notably the globules of oleaginous, amber-like resin streaked with traces of paint to be found in drips and clumps on the floor of the glasser’s bay – but also from a childhood preoccupation with marbles (habitually viewed in perpetual rolling motion). ‘I could stare for hours at the twisting strokes of pigment caught in their interiors. It was like looking at a moment caught in time. A frozen gesture that might just reactivate and start back in motion if you kept staring for long enough.’

Adopting a strategy of sampling and remixing as a fluid means ‘of developing aesthetic and conceptual frameworks’ (a methodology familiar from the work of contemporary electronic musicians), Lock’s luscious impasto brushstrokes on stark (unaltered), retina-dazzling holographic grounds – exhibited in 2003 at Greenaway Art Gallery – quoted from Lichtenstein’s brushstroke works, such as Yellow Brushstoke I (1965). Devoid however of Lichtenstein’s satirical intent and with characteristically charismatic titles such as Poison Apples for Longing Lovers or Too Good to Tango With the Poor Boys, they effectively represented a joyous valorisation of the gestural brushstroke.

For Lock these optically assertive paintings also indicated a satisfying synthesis or hybrid of the organic gesture, a digitalised electronic version of the modernist grid and a smooth flawlessness of surface – a straddling therefore (rather than a collision) of organicist and mechanicist modes of abstraction. Although it must be noted that the holographic grids – electrifying in their brilliant, ever-fluctuating hues – did appear to hover on the precipice of chaos. The holographic material is also of course, a readymade and in his 2003 Mellon series of lectures, Kirk Varnedoe noted the significance of such unexpected hybrids – of the blending of ‘strains from seemingly opposite camps’ – in the forging of ‘important new artistic1 languages.’5

Endnotes

1. Timothy Leary, ‘The Evolutionary Surfer’, interview with Steve Pezman, SURFER, Jan. 1978

2. Steven Levine, ‘Seascapes of the Sublime: Vernet, Monet and the Oceanic Feeling’, New Literary History, 1985, p. 380

3.Steve Pezman, ‘The Evolutionary Surfer’, SURFER, Jan. 1978

4. All Christian Lock quotes (henceforth unnumbered) are from 2007 interviews with Wendy Walker

5. Kirk Varnedoe, Pictures of Nothing, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton Uni Press, 2003, p. 7. Varnedoe is referring to the (historical) overlapping and blending of strains from the seemingly opposite camps of Johns and Pollock, or Picasso and Duchamp.

6. For Anthony Haden-Guest the monochrome painting was ‘the great Modernist icon of the sublime, involving Burke’s privations in the fact that all detail and differentiation has disappeared from the world of vision.’ Lock proposes a contemporary ‘fictitious model of the techno-sublime that incorporates the gesture.’

Anthony Haden-Guest in Sticky Sublime, Bill Beckley (ed), NY, Allworth Press, 2001, p. 72

7 Cited in Gabriel Ramin Schor, ‘Black Moods’, the Latin title is Utriusque cosmi, maioris scilicet et minoris, metaphysica, physica, atque technica historia http:// www.tate.org.uk/tateetc/issue7/blackmoods.htm

/ 2005

Since the late nineties, the art of Christian Lock has consistently inquired into painting’s position and relevance in contemporary visual culture, and its relationship with other media and technologies.

Lock’s artistic enterprise has been fuelled by an ambitious attempt to reassess and rejuvenate the pertinence and possibilities of painting in an era marked by the predominance of electronic technologies (cinema, television, video, cyberspace), and the proliferation of a vast variety industrial, mass-produced surfaces 1.

The canvases and mixed-media works compiled for this exhibition are the most recent fruits of a dynamic and constantly expanding practice; one that has merged Lock’s proficiency as a painter with his experience as a sculptor and surfboard manufacturer. This innovative, interdisciplinary approach has, to date, spawned astutely conceived and superbly crafted artworks distinguished by their striking scale, format, exquisite melange of media, and dazzling juxtaposition of complementary patterns and gestures.

Take witty, wonderfully-titled works like She Cost Me a Spot in the Team(2005) and She Won the Heart of a Contract Killer (2005), which utilise MDF supports, holographic and computer-generated reflective surfaces, acrylic paint and polyester resin. The contrasting forms, gestures, colours and surfaces which collide and coexist.

Respectively, Owens cites photography as a cogent exemplar of allegorical art, one that represents the desire to fix the transitory and ephemeral in a stable and stabilising image. Another indispensable impulse in allegory is its capacity to confuse and blur the rigid boundaries separating aesthetic mediums and stylistic categories. “The allegorical work”, Owens observes “is synthetic; it crosses aesthetic boundaries; this confusion of genre...reappears 8 today in...eclectic works which ostentatiously combine previously distinct art mediums” .

These various allegorical impulses - the appropriation and recontextualisation of images, the suspension of movement and continuity, and the synthesis of previously distinct mediums – are beautifully negotiated and transformed in Christian Lock’s canvases and polyester resin slabs and tablets. In canvases like Return to the Promised Land (2005) and New Fighting Words (2005), one encounters nebulous, unwieldy flower- or vulva-like apparitions that recall the biomorphic forms found within the imagery of Modern artists like Andre Masson, Juan Miro, Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky and others. Lock’s elusive, spray-painted, and spectral, forms with their irregular, wrinkled, concentric rings shift and mutate with each reproduction, resembling portals or voids, or alternatively, burgeoning and wilting supernovas.

Comparatively, Lock’s opulent and opaque, cola-coloured reliefs such as Living like a Rich Kid (2005) and Poison Apples for Longing Lovers (2005) mimic the accentuated and grandiose shapes of gothic and baroque mirrors, and appropriate two exemplary formal elements of Modern painting, the brushstroke and the grid. The former was once regarded as an unmediated marker of an artist’s spontaneity, authenticity, emotion, and personality , whilst the latter proved to be a more ambivalent, multivalent and “schizophrenic” structure signifying both rigid materialism and transcendental spirituality. Lock’s synthesis of these contrasting signs throughout his resin-based artefacts is partly indicative of an attempt to reconcile what Donald Kuspit sees as the historically volatile relationship between an organicist abstraction based on the brushstroke and a mechanicist one 11 premised on the grid.

But the encasing of brushstrokes in translucent layers of resin seems to conjure the allegorical desire to suspend the transitory and ephemeral in a stable image. Indeed, one can discern a sense of transience, fluidity and flux in Lock’s artefacts that is simultaneously be arrested, embalmed and preserved...a manoeuvre analogous to the idiosyncratic operation of photography.

However, it is perhaps the final allegorical impulse that cogently encapsulates the novelty and ingenuity of Lock’s eclectic aesthetic: namely the capacity of his art to confound the boundaries between aesthetic mediums 12 and stylistic categories via the blending of supposedly distinct mediums . The joyful, exuberant complicity of Lock’s practice with what Clement Greenberg regarded as the “spurious” Other of Modernist painting (i.e., ersatz culture, industrial techniques, mass-produced commodities), is precisely what enables his work to both revitalise the basic constituents of painting and, more significantly, relate to the surfaces and processes of other media: photography, television, video...and music.

Contemplating Beautiful Days (2005), with its multiple plateaus of broad, buoyant brushstrokes and its glittering grid of golden orbs, I think of the retro-chic styling and neon lighting of discothèques and the pulsating rhythms of electronica, particularly the dinky melodies of Daft Punk. For me, the lush, lavish strokes overlaid onto the luminous holographic lattice are the visual counterparts to the French dance duo’s distinctive brand of techno: wiry, buzz-saw guitar riffs superimposed onto crisp, taut, motorised electro-funk loops and boppy, slinky samples. In the alluring, multifaceted art of Christian Lock, painting does not confine itself to its own limits in the in these works elicit a plethora of phenomena: the “seductive sheen” specimens.

Varga Huseini

2 of commodities, the iridescent glow of neon lighting, and the cold, clinical glare of microscopic

1. M. Kutschbach, ‘Stuff in Flux: An Exploration of Uncertainty within Surfaces as the Result of a Material Based Painting Practice’, Masters Thesis, University of South Australia, 2004, p.4.

2. L. Mulvey, ‘Some Thoughts on Theories of Fetishism in the Context of Contemporary Culture’, in October, no.65, Summer 1993, p.10.

3 C. Owens, ‘The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism’, in October, no.12, Spring 1980, p.68.

4 ibid., p.68.

5 ibid., pp.68-69.

6 ibid., p.69. 7 ibid., p.69.

8 ibid., p. 75.

9 D. Hickey, Roy Lichtenstein Brushstrokes: Four Decades, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, 2001, p.15. See also J.A. Hobbs, Art in Context, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Diego, New York, Atlanta, Washington.

10 R. Krauss, ‘Grids’, in October, no.9, Summer 1979, p.60 & p.64.

11 D. Kuspit, ‘The Abstract Self Object’, in F. Colpitt (ed.), Abstract Art in the Late Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002.

12 Owens, p. 75.

13. J. Derrida, ‘Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences’ in Writing and Difference, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1978, p.292.